The outsider: artist and curator Matías Sánchez

Matías Sánchez in his studio

The self-taught contemporary Spanish painter Matías Manuel Sánchez Martín (b. 1972, Tübingen, Germany) is known for his whimsical, expressionist portrayals of wild, unique characters rendered with a thick, colourful impasto. Represented by Galerie Zink, the same gallery that was amongst the first to represent both Yoshitomo Nara and Javier Calleja, Sánchez’s work can also be found in the public and private collections of the CAC Malaga; the S. Goodman Collection, New York; the Art Museum of the University of Southern California; and Benetton Art Spain Collection, amongst others.

Sánchez is perhaps one of the best known contemporary ‘outsider artists’ in the art world. ‘Outsider art’ (also known as art brut, or ‘raw art’ in French) was a term popularised by the modernist French artist Jean Dubuffet, who from 1964 began to collect artworks whose “instinct, passion, mood, violence, madness”[1] channelled sincere and real expressions of a vision or emotion, free from societal constraints. Possessing a naïve, childlike simplicity, ‘outsider art’ was often produced by self-taught artists (including children, outsider and folk artists, as well as the mentally ill) who worked outside the conventional structures of art training and art production. Praising the “anticultural position”, Dubuffet urged people to discard their preconceived notions of beauty:

“Look at what lies at your feet! A crack in the ground, sparkling gravel, a tuft of grass, some crushed debris offer equally worthy subjects for your applause and admiration.” - Jean Dubuffet[2]

Although Sánchez conjures up a comical cast of bulbous-nosed and wonky-eyed artists on the margins of society in the works he has created for this exhibition, a deep understanding and love of artistic traditions inspired by icons such as diverse as Rembrandt, Pablo Picasso and Willem de Kooning underlies his work. Banal, comical, cryptic - Sánchez’s works touch upon movements as diverse as 19th-century Realism and vanitas painting, bringing together a tongue-in-cheek iconography of cartoon skulls, bones, tufts of grass and scribbled dark clouds, which rub shoulders with grinning rats (El viejo pintor y sus detractores, or ‘The old painter and his detractors’), overflowing paint palettes (Au plein air, or ‘Outdoors’), and meaty sausages (Pintores en el campo, or ‘Painters in the field’). Like the French Realist painter Gustave Courbet, whose ‘unfinished’ and ‘vulgar’ portraits of everyday peasants and workers challenged academic ideas of ‘high’ art at the time, Sanchez expresses the harsh reality of life with spontaneous and rough handling of paint, his band of crude, clownish protagonists exuding a menacing yet poignant air.

“The important thing is how that painting is painted and how it seduces the viewer. The intelligence of the execution, its mastery, how the artist manages the viewer’s perspective from where he wants. Where does the viewer enter the painting, walk through it. and then exit? Those are the things that make a work of art timeless.” - Matías Sánchez

Top: Gustave Courbet, The Meeting or "Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet", 1854

Collection of Musée Fabre, Montpellier

Bottom: Matías Manuel Sánchez Martín, Au plein air, 2022

Left: Gustave Courbet, The Hunt Breakfast, 1858

Collection of Wallraf–Richartz Museum, Cologne

Right: Matías Manuel Sánchez Martín, Pintores en el campo, 2022

“Smart Idiots”: exhibition overview

Derived from the famous Goldwynism “Give me a smart idiot over a stupid genius any day”[3], Matías Sánchez weaponises the oxymoronic, derogatory label “smart idiot”. Sánchez transforms the show’s title into a subversive badge of pride, overturning all preconceptions by bringing together a group of artists who re-interpret the conflict between so-called ‘high’ and ‘low’ artistic cultures. In each work the viewer is confronted by a discordant clash between subject matter and style, whilst taunted by a gleeful bait-and-switch between the pull of the familiar and the sharp shock of the unexpected.

Materiality and texture bordering on sensuousness is present throughout the show: from the ridged impasto paintings of Cristina Lama Ruiz, Dan Schein, and Gregory Forstner, to Paco Pomet’s hyperreal monochromatic canvases and Klaas Rommelaere’s intricate tapestries. Despite the variety of artistic styles on view, each artist showcases an innate understanding of colour, line and form, with tactile, rhythmic brushstrokes and jewel-bright tones that arrest the viewer from across the room.

Each artist also displays a rigorous understanding of art history and popular culture, with each of their works revealing multilayered stories and references that unfold upon closer inspection: anatomical skeletons, plant diagrams, fashion models and fragmented texts are patchworked together by Klaas Rommelaere; Dan Schein playfully fakes stories from the Bible; Cristina Lama Ruiz manifests her preoccupation with memento mori and the occult; Gregory Forstner creates absurdist historical portraits; and Paco Pomet painstakingly renders a surreal dialogue between painting and photography.

Paradoxes: a closer look

Real / surreal: Paco Pomet (b. 1970, Spanish)

The Spanish artist’s austere hyperreal oil paintings, inspired by his collection of vintage photos from the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, are disrupted by surreal motifs and startling chromatic eruptions. Humour in Pomet’s work is tempered by realism, in particular an attitude of cynical resignation regarding politics and current affairs: “I happen to like realism precisely because I tend to be very observant, even though I’m more critical with reality. [...] A slight misanthropic drift has imbued many of my themes lately, however, a bright and clean humorous streak can appear dressed up in oil paint at any moment!”[4] The result is a contemporary take on Surrealism reminiscent of the irrational, black humour of his compatriot Salvador Dalí. Pomet’s intrepid soldier vaults over a stretched canvas with one hand in Infantry, illuminated by a neon orange-tipped paintbrush that he brandishes like a rifle over his other shoulder. Infantry thus offers a pithy and provocative contemplation about the “soft power” of art versus traditional coercive or violent means, that can alternately be read as a mock-valorisation of the contemporary artist’s struggles.

Left: Philippe Halsman, Dali Atomicus, 1948

Right: Paco Pomet, Infantry, 2022

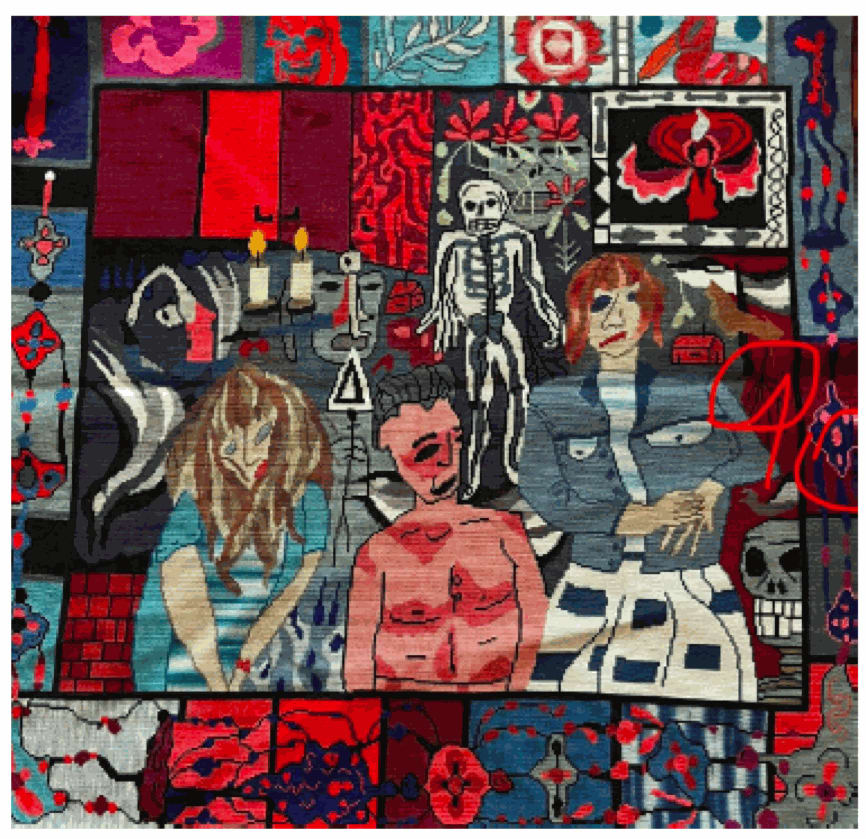

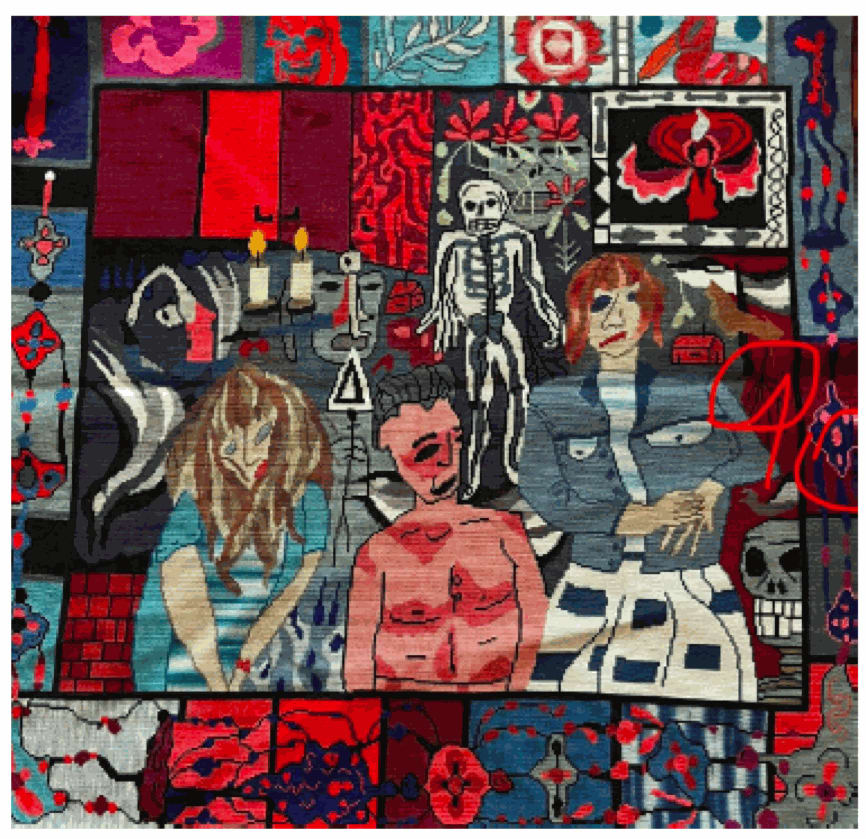

High / low: Klaas Rommelaere (b. 1986, Belgian)

The Antwerp-based artist’s surreal embroidered scenes use traditional cross-stitch, crochet and knitting techniques and are executed by his team of ‘madames’ scattered across various Belgian towns. Originally from the fashion world, Rommelaere’s unorthodox works subvert the notion of textile art as a “lowly” decorative craft form; instead, Rommelaere approaches the medium with a reverence and originality customarily devoted to high art. Brightest Star and Smart Idiots showcase the phenomenal breadth of Rommelaere’s fantastical inner world: surreal computer glitches, warped anatomical diagrams, excerpts from movies and graphic fragments of the artist’s personal memories are literally woven into each work. “I document and transcribe my existence consciously through my work. Comparing this to social media, for example, I am not posting my personal life on there. I deal with it through my work. It is a kind of therapeutic medium for me,” muses the artist.[5] Rommelaere also celebrates rather than obscures the contribution of his community, frequently acknowledging his female collaborators and how their different visions of beauty bring richness and depth to each of his works.

Top: Flemish 16th Century, The Return from the Hunt, c. 1525–1550. Collection of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

Bottom: Klaas Rommelaere, Smart idiots, 2022

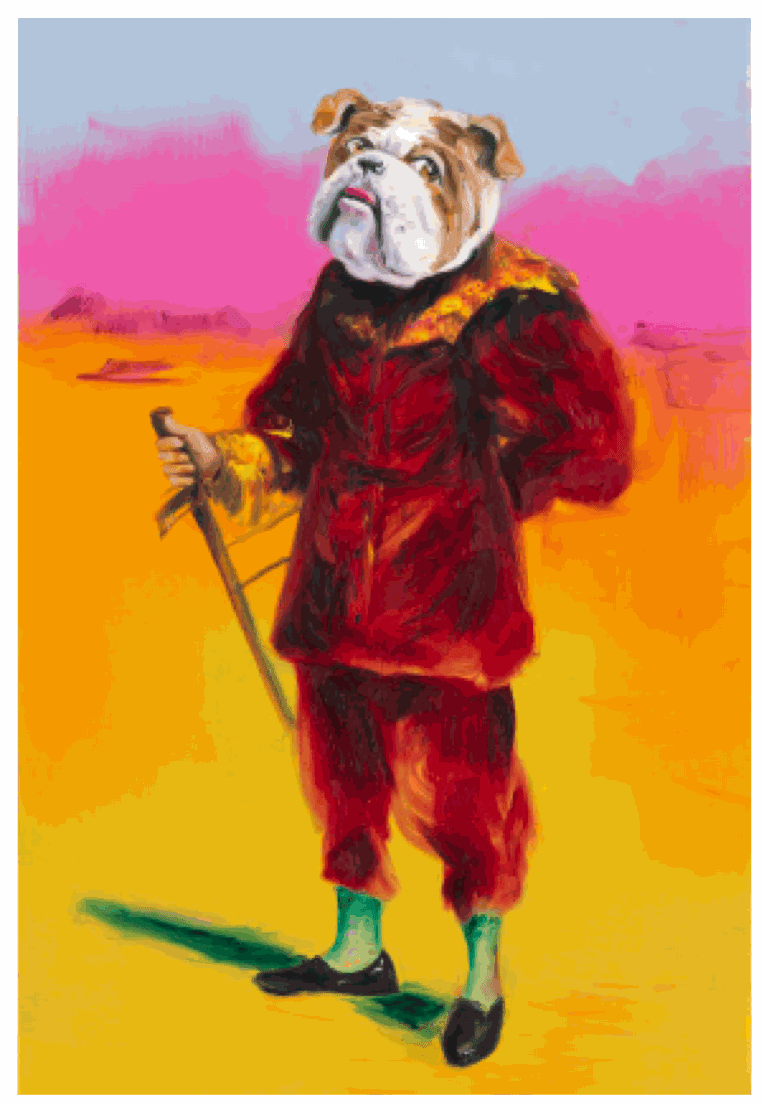

Rational / irrational: Gregory Forstner (b. 1975, French-Austrian)

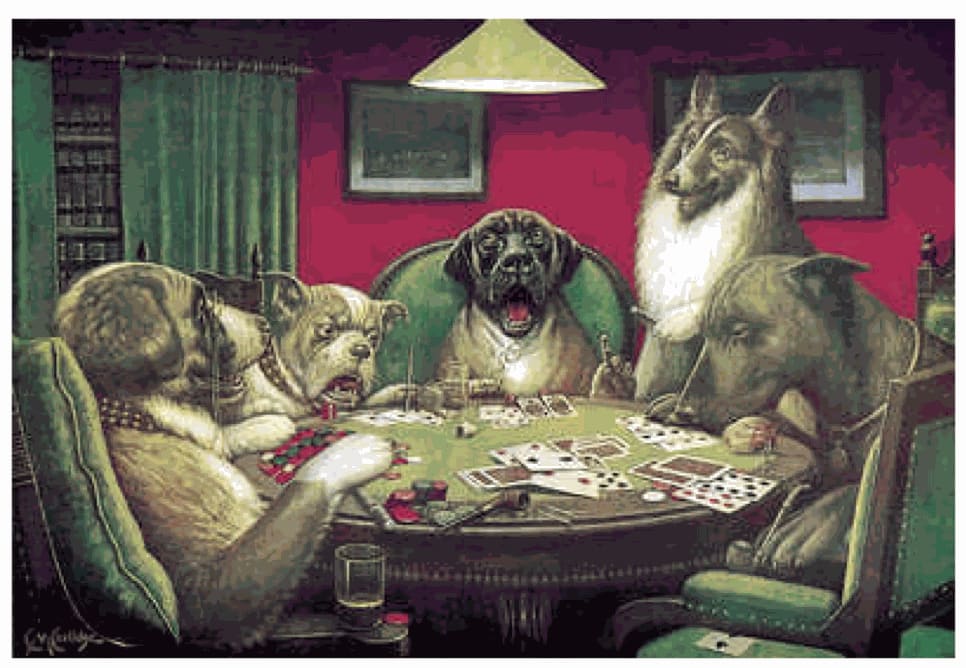

Inspired by American illustrators Arthur Sarnoff and Cassius Marcellus Coolidge, Gregory Forstner has incorporated dogs into his satirical scenes since 2006. Forstner theorises that dogs, with their history of caricatures in print, benefit from immediate recognition by the viewer’s subconscious, and he uses these avatars to provoke eye-opening sensations and reactions from his audience using shared cultural and historical contexts. Sometimes they gather around a billiards table; at other times they appear dressed in SS and Wehrmacht uniforms in reference to Forstner’s own dark family history. Forstner’s array of anonymous canine protagonists elicit a mixture of amusement and trepidation: whimsical, colourful forms rendered with loose, painterly brushwork clash with recollections of cruel and violent periods in history. Untitled and Untitled (1) (2019) draw on Forstner’s love of the Dutch Golden Age painters Frans Hals, Jan Steen, Adrian Brouwer, whose portraits and genre works depicting human behaviour in everyday environments were known for their psychological insight, humour and vivid use of colour. Forstner’s paintings tap into “a common history from which a certain relation to the world asserts and questions itself, especially through memories and history told by ‘fathers’. It is, amongst other things, a principle of transmission and interpretation, it is questioning the way a subject creates itself from this memory”.[6]

Top left: Cassius Marcellus Coolidge, Waterloo, circa 1909

Top right: Frans Hals, Laughing Cavalier, 1624. Collection of the Wallace Collection, London.

Bottom: Gregory Forstner, Untitled (1), 2019

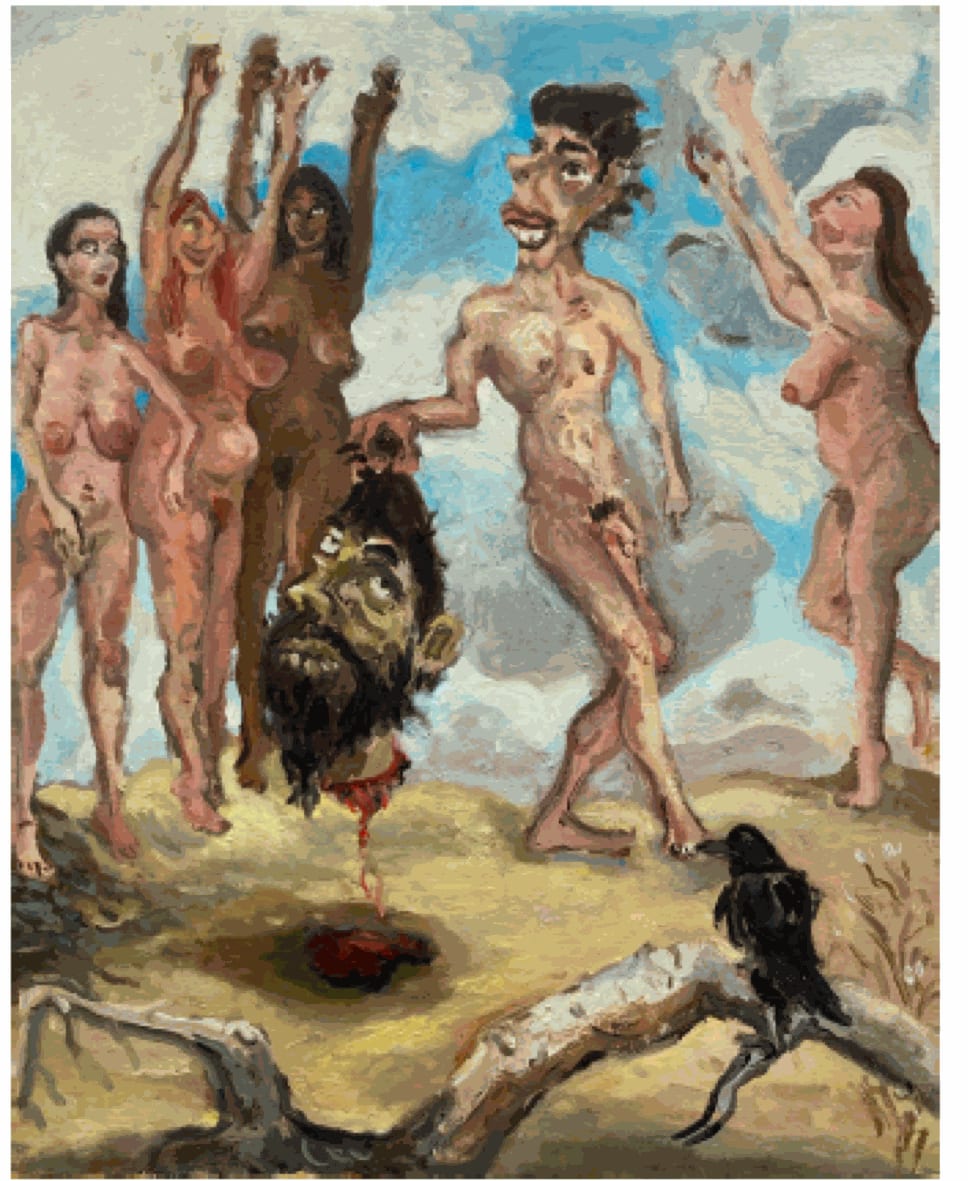

Sacred / abject: Dan Schein (b. 1985, American)

Schein offers a visceral, twisted take on the Biblical story of David, the young shepherd who gains fame by slaying the giant Goliath, champion of the Philistines, and later went on to become King of Israel. In orthodox Christian iconography, David and Goliath symbolise the battle between Christ and Satan and the triumph of good over evil. But whereas traditional renditions of this scene (for example by Caravaggio) have depicted a heroic David deeply moved by the death of his enemy, Schein recasts the roles of hero and monster over five imaginary scenes. The stone is credited as the protagonist as it arcs from the sling of David towards Goliath’s head (Sling Shot the Bully), whilst a merciless David raises his sword to kill and dismember his enemy (David the Honorably Violent and Removal of Limbs). In the next scene, a gloating, naked David parades the severed head of Goliath to a chorus of adulation from a group of buxom female admirers, whilst a crow observes the scene ominously from his foreground perch (David’s False Retelling of his Deeds). The finalere-examines the role of the victim, with Goliath’s head illuminated like a haloed saint on a platter (Goliath the Fearsome).

Executed with a magma of pure pigments loaded directly onto the canvas (often without a preparatory sketch), Schein overwhelms and disfigures his subjects as the series progresses to its gory climax. This cruel and callous David morphs into a caricature with brutal, disorienting strokes. In Schein’s world, the underdog becomes the oppressor, and the corruptive cycle of power continues. “I guess I wanted to create powerful imagery that's humanistic but also, cynical but not! if that makes any sense. Not necessarily condemning acts but just trying to tell little stories with each painting,” explains the artist.[7]

Top: Neapolitan School, David and Goliath, 17th century

Bottom: Dan Schein, David the Honorably Violent, 2021-22

Top: Caravaggio, David with the Head of Goliath, circa 1610. Collection of Galleria Borghese.

Bottom: Dan Schein, David’s False Retelling of his Deeds, 2021-22

Death / rebirth: Cristina Lama Ruiz (b. 1977, Spanish)

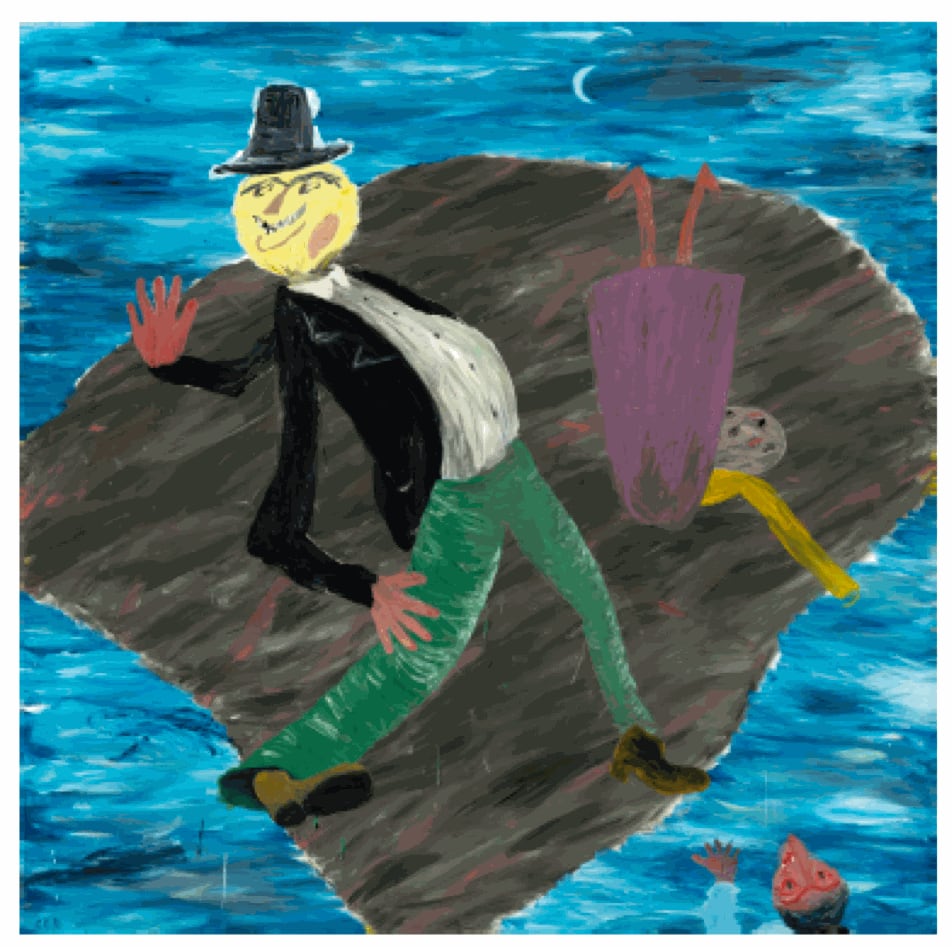

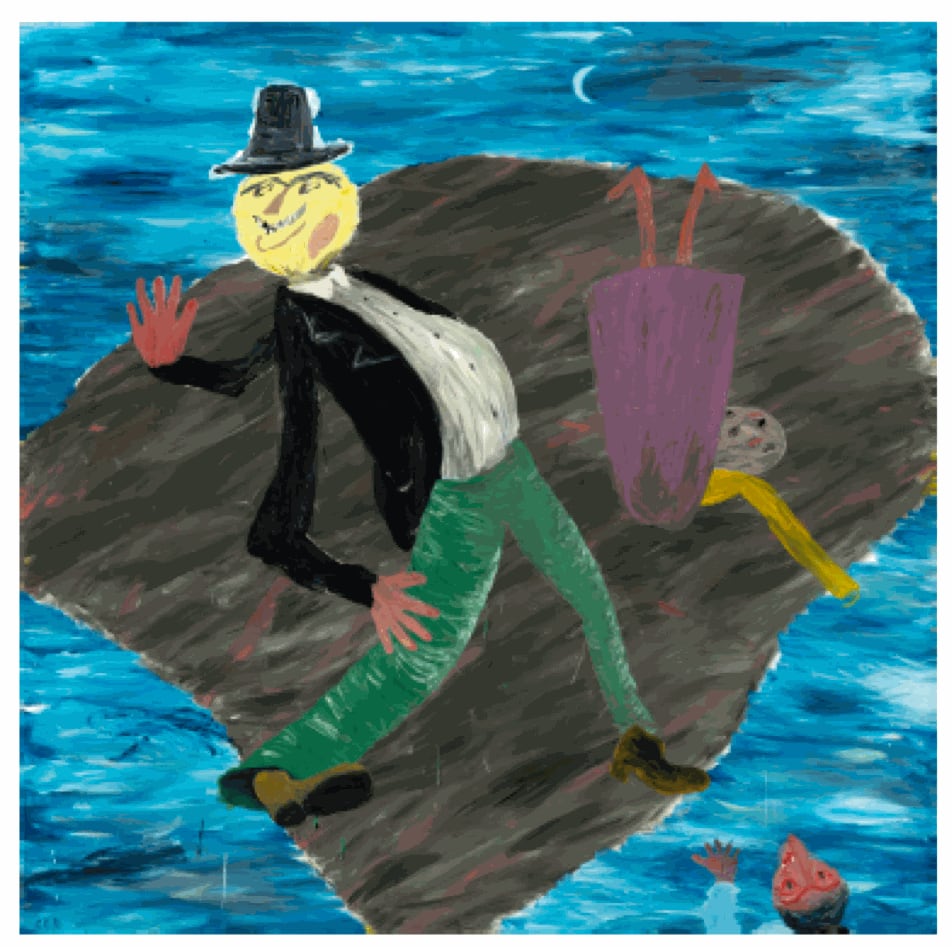

Like fellow Spaniard Matías Sánchez, a morbid sense of humour ripples through Lama Ruiz’s works:in Peleles (‘Dummies’) a top-hatted man pushes women off a raft in the middle of the sea, a mocking riposte to the genre of Romantic shipwreck scenes such as Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa; El Brujo(‘The Wizard’) depicts the floating head of a warty, hook-nosed sorcerer and a cartoon bat suspended from the upper edge of the blood red canvas; meanwhile, Imprescindibles(‘Indispensables’) portrays a thicket of grinning skulls surrounded by wilting flowers. Lama Ruiz conjures up a nightmarish, childish iconography of bats, skeletons and witches, whilst touching upon childhood terrors and fears with a tenderness and irony that turns preoccupations with death and the occult into encounters with acceptance and humour. Executed with swift, expressive strokes that leave richly coloured, heavy impasto daubs on the canvas, Lama Ruiz’s painting process betrays a fascinating psychological complexity that draws the viewer into her world. Lama Ruiz’s energetic gesturalism proclaims a fresh message of hope and life - carpe diem - transforming the genre of the vanitas painting from a contemplation of death and desolation into a celebration of childhood, everyday life, art and literature.

Top: Théodore Géricault, The Raft of the Medusa, 1818–19

Bottom: Cristina Lama Ruiz, Peleles, 2022

[1] Jean Dubuffet, “Anticultural Positions” (1951), reprinted in J. Dubuffet (New York, 1960), p. 192

[2] Jean Dubuffet, "Empreintes", in Herschel B. Chipp, ed., Theories of Modern Art: A Source Book by Artists and Critics (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1968), p. 611

[3] Samuel Goldwyn was a US film producer renowned for his comical and supposedly unintentional misuse of idioms.

[4] Paco Pomet quoted in Gwynned Vitello, ‘Paco Pomet: The Surrealist Adventurer’, Juxtapoz, online

[5] Klaas Rommelaere quoted in Emma Smit, “Klaas Rommelaere: A Patchwork Diary”, Metal Magazine, online

[6] Gregory Forstner quoted in Jonathan Mok, ‘Inspired by Nazi horror: an interview with Gregory Forstner’, Global Comment, 17 June 2010, online

[7] Dan Schein quoted in Shanna Waddell, “Dan Schein - Artist Interview”, Shanna Waddell Blogspot, 15 November 2011, online